The International Conference on Disabilities in Africa (ICDA) has come and gone on the 28th of July 2018, in Abuja, Nigeria, but not without featuring a poster presentation from our research team. The poster authored by Emma Asonye, PhD., Ezinne Emma-Asonye and Joy Jenyo discussed the factors that have continued to fan the embers of stigmatization for deaf children in Nigeria and children with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

The factors, which have been identified in the course of our research in Nigerian deaf community over the past four years include but not limited to:

- Language and Communication Barrier

- Cultural Orientation

- Family Dis- or Misinformation

- Poor Education System

- Inadequate Studies and Training for Professionals

As we know that some of these factors may have been discussed by various scholars at different times, one thing that stands out for us in this study is the first-hand experiences we have had of these factors during our outreaches over the past four years. Many would agree that language and communication barrier is a typical challenge with deaf children and adults in Nigeria, but how about children with IDD? First, we observed that Deaf and individuals with IDD are both framed as People with Disabilities (PWDs), and in many inclusive Deaf schools we have visited, deaf children and children with other disabilities make up the population, even in some mainstream schools (with hearing students), deaf students and students with IDD are placed in the same units and classes, away from the hearing students, where they are all taught with signed language or through interpretation by a signing teacher. The first impression a visitor gets on getting to these schools is that all the students are deaf, until you hear one student make a clear utterance, and the first question you will ask is, “are you also deaf?”, and you will hear another vocal response, maybe to your deeper surprise, “No.”

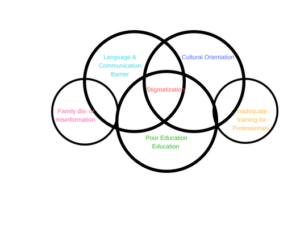

Another significant issue that this study intends to reveal is how all the above factors and more that are not discussed in this paper are interrelated – one touching the other as illustrated in the diagram below.

In a Deaf-Hearing mainstream school in Abuja, we recorded a hearing student in one of our outreaches in 2017 as he narrated how he was warned by his parents to beware of the deaf students when he gets to school. His mother instructed him to stay away from the deaf students, so he doesn’t become deaf. According to the boy, until that day, he had obeyed his parents’ instructions by maintaining a distance with the deaf students. He seemed not to have heard a contrary information until that day our outreach team visited the school with a different message.

This attitude by the boy’s parents could have been informed by the cultural orientation that regards all deaf persons as ‘sick’ and probably ‘infectious’, or even by family dis- or mis-information (family members having no or the wrong information about deafness), or a combination of both, sustained by a poor education system that separates deaf from hearing students even when they are placed in the same school, plus the fact that greater number of the teachers in that school may not be Special Ed or Deaf Ed trained, who also may have come from the same cultural orientation that stigmatizes deaf people. The result of all this is an example of what we witnessed in the school in Abuja, which is not different from what obtains in Imo, Lagos, Enugu, Rivers, where we have had our outreaches and study.

For children with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD); well the term IDD is not yet a common term for average Nigerians, but different languages spoken in the country, no doubt have a names for people with such challenges that frame them with everything negative. The word autism, for instance, is still a ‘big word’ in the dictionary of a typical Nigerian; Down Syndrome, cerebral palsy all mean everything but positive. We are not aware of how many indigenous languages that have different names for all these other than a common name that connotes negativity. We know that in a typical traditional setting, education is hardly for such children, but one would wonder why the modern education created a system that creates a classroom for deaf students and students with IDD. These are some of the issues our present study wishes to examine, and so it goes further to ask the following questions:

- Do deaf children and children with IDD have the same kind of disability?

- Put in another way, could people with IDD be regarded as a linguistic minority or cultural minority group like the Deaf?

- Placing deaf students and students with IDD in the same classroom, away from hearing students in the same school, is it a true way of inclusion?

- Do deaf students and students with IDD learn at the same pace?

These and many other questions continue to seek answers as far as our study is concerned.